PELAKITA.ID – Environmental inequality does not only occur at the national level, but also on a global scale.

This is precisely what makes political ecology so relevant: it not only highlights conflicts over access to and control of resources in particular villages or forests, but also exposes the global structures that position developing countries as providers of raw materials and as bearers of ecological burdens, while developed countries reap the economic benefits with far higher levels of consumption.

One of the main features of global capitalism is its ability to externalize environmental costs.

As David Harvey (2003) explains through his concept of “accumulation by dispossession,” capitalism sustains itself by appropriating resources from marginalized communities and displacing ecological burdens onto them.

Developed countries often maintain the quality of their domestic environment by “exporting” ecological burdens elsewhere.

This process takes place through commodity trade, relocation of polluting industries, and the design of global institutions that are biased toward the interests of the Global North.

For example, the palm oil industry in Southeast Asia has grown rapidly not merely due to local demand, but primarily to meet the need for cheap vegetable oil in European, U.S., and Chinese markets.

As Alf Hornborg’s (2011) theory of “ecological unequal exchange” highlights, such global trade relations disguise an asymmetry: energy and material resources flow disproportionately from the Global South to the Global North, while ecological degradation remains concentrated in the South.

Developed countries may claim to be “greening” their economies, but the ecological footprint is effectively shifted elsewhere.

The REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) program is often cited as a concrete example of how global conservation-oriented policies can produce new inequalities.

In theory, REDD+ is designed to provide incentives to developing countries to protect their forests, in exchange for funding from developed countries seeking to offset their carbon footprint. Yet in practice, the program often results in land grabbing under the guise of conservation.

This illustrates what James Fairhead, Melissa Leach, and Ian Scoones (2012) call “green grabbing”—the appropriation of land and resources in the name of environmental conservation.

Indigenous peoples who have safeguarded forests for centuries are suddenly deemed “illegal” because they lack formal land certificates. Once their territories are included in REDD+ schemes, access to land, timber, and even traditional cultural practices becomes restricted.

Meanwhile, developed countries can postpone energy transitions at home because they feel they have already “purchased the right” to protect forests elsewhere.

In other words, conservation framed as a market mechanism ends up reproducing colonial power relations: the Global South provides environmental services, while the Global North continues to control the transition agenda.

Global inequality is also evident in carbon trading. In theory, carbon trading allows companies in developed countries that struggle to cut emissions to purchase credits from conservation or renewable energy projects in developing countries. In practice, however, this often entrenches injustice.

Large corporations in Europe or the U.S. can keep polluting by buying cheap credits, while local communities in credit-supplying countries gain little to no meaningful benefit. Larry Lohmann (2010) has critiqued carbon markets as “neoliberal fixes” that commodify the atmosphere while displacing the burdens of climate mitigation onto the South.

Ironically, carbon trading is frequently portrayed as a “win-win” mechanism. Yet, from the perspective of political ecology, the benefits flow mainly to multinational corporations, financial institutions, and international brokers, while local communities most affected by climate change remain excluded from economic gains.

In some cases, carbon projects even become grounds for prohibiting communities from opening land or practicing traditional agriculture, even when they only use resources for subsistence.

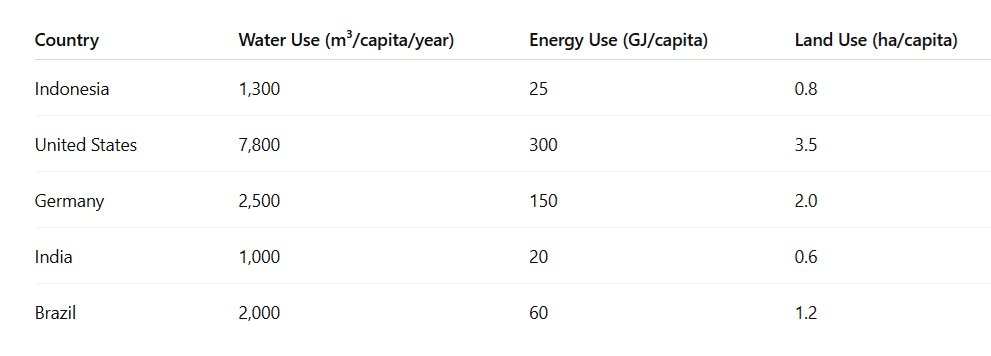

Global inequality can also be understood by comparing per capita resource consumption between developed and developing countries. The following data illustrate the gap:

This table shows that per capita consumption of water, energy, and land in developed countries far exceeds that of developing nations. An average American, for instance, consumes 12 times more energy than an Indonesian, and nearly 15 times more than an Indian.

Similarly, land use: the average American requires 3.5 hectares to sustain their lifestyle, while an Indonesian requires only 0.8.

These figures reveal a deeply uneven ecological footprint. Developed countries sustain high consumption, while ecological degradation is often borne by other nations that supply cheap commodities.

This is what Martínez-Alier (2002) terms the “ecological debt” owed by the Global North to the Global South.

The inequality becomes even clearer when we look at the impacts of climate change. Developing countries, whose contributions to greenhouse gas emissions are relatively small, are in fact the most vulnerable.

Pacific island nations, for example, face existential threats from rising sea levels, even though they have contributed almost nothing to cumulative global emissions.

Indonesia, too, is experiencing more frequent hydrometeorological disasters—floods, landslides, forest fires—as a result of climate change, despite its per capita carbon footprint being far below that of developed nations.

This phenomenon reflects what is known as “climate injustice” (Roberts & Parks, 2007): the paradox in which those who contribute the least bear the greatest burdens.

Meanwhile, developed countries often position themselves as leaders of the global climate agenda but are reluctant to significantly reduce their domestic consumption.

Political ecology allows us to interpret these inequalities as a new form of colonial relations. The concept of ecological unequal exchange explains how developing countries export vast amounts of resources at cheap prices, while developed countries import the benefits and export waste and pollution.

Through a neo-Marxist lens, this situation can be seen as a form of “accumulation by dispossession” on a global scale. Forests, water, and land in the Global South are reduced to commodities to sustain the consumerist lifestyles of the Global North.

Developing nations are often pushed—or forced—into export-oriented development models, while their ability to protect local communities and ecosystems becomes increasingly constrained.

Global inequality in political ecology is not just a matter of statistics, but a lived reality for millions across the developing world. REDD+, carbon trading, and resource consumption data all show that despite the rhetoric of sustainability, global structures remain deeply uneven.

Developed nations continue excessive consumption, while developing countries are compelled to shoulder ecological and social burdens.

Political ecology, with its critical framework, helps expose this paradox. It shows that global sustainability cannot be achieved without addressing the structural injustices between North and South.

Without fundamental changes in developed countries’ consumption patterns and in the global trade system, conservation and energy transition programs risk becoming mere “green cosmetics,” masking new forms of dispossession.

References

-

Harvey, D. (2003). The New Imperialism. Oxford University Press.

→ Introduces the concept of accumulation by dispossession as a driver of global inequalities, including ecological ones. -

Hornborg, A. (2011). Global Ecology and Unequal Exchange: Fetishism in a Zero-Sum World. Routledge.

→ Explains ecological unequal exchange, showing how resources flow from the Global South to the Global North. -

Martínez-Alier, J. (2002). The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation. Edward Elgar.

→ Develops the idea of ecological debt owed by the North to the South. -

Fairhead, J., Leach, M., & Scoones, I. (2012). Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature? Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 237–261.

→ Introduces the concept of green grabbing, relevant to REDD+ and conservation-driven land appropriation. -

Lohmann, L. (2010). Uncertainty Markets and Carbon Markets: Variations on Polanyian Themes. New Political Economy, 15(2), 225–254.

→ A key critique of carbon trading as a neoliberal “fix” that reproduces inequalities. -

Roberts, J. T., & Parks, B. C. (2007). A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North–South Politics, and Climate Policy. MIT Press.

→ Defines climate injustice, explaining how those least responsible for emissions are most vulnerable. -

Blaikie, P., & Brookfield, H. (1987). Land Degradation and Society. Methuen.

→ Foundational text in political ecology, analyzing how social and political structures shape environmental outcomes. -

Peet, R., Robbins, P., & Watts, M. (Eds.) (2011). Global Political Ecology. Routledge.

→ Brings together global case studies of power, capitalism, and environmental change.